Reading a Place with Liv Gussing Burgess

Across luxury hospitality and guest facing industries, you can find the same structural tension: the widening gap between what brands intend with mission statements or brand guidelines and what teams can execute. Concepts are ambitious, language is refined, and standards proliferate, yet often something essential fails to transfer.

Speaking with Liv Gussing Burgess - more than twenty years in ultra-luxury hospitality, fourteen of them with Aman Resorts under founder Adrian Zecha, since then consulting independently - clarified the mechanics of this breakdown.

Starting Outside

Liv begins any foreign project by going outside. Walking or running through a neighbourhood before opening a single document gives her information most briefings omit: how people occupy space, where energy concentrates or thins, how formality functions in daily interactions. Ten countries across four continents have trained her to build internal maps through movement. Small encounters, buying water, exchanging a few words, supply the social cadence that later shapes operational decisions.

She mentions being mistaken for Moroccan in Marrakech, Tahitian in Tahiti. She describes it as “being a chameleon,” but what she is actually practicing is perceptual calibration: aligning herself to a context so she can read it correctly. This registers immediately. I have travelled on my own since the age of seventeen, and learning to enter unfamiliar environments required the same instinct: adjusting just enough to understand how a place works and how to move through it without interrupting its rhythm.

Liv’s career at Aman Resorts began as front office manager at the Strand in Yangon. After seven years she became general manager at Amandari Bali, taking on multiple hotel openings between and spending four to twelve months embedded in each property.

"Aman shaped everything I know about brand," she says, "from its DNA to living it in every interaction." That foundation, understanding how brand translates into lived operational reality, became what she now brings to clients.

Distant Viewpoint

Liv’s move from managing Amandari Bali to consulting changed the angle of observation. “In operations, you’re inside the day-to-day. Consulting lets you step back and see how the parts fit together.” With that distance came a clearer view of where concepts and vision can get stuck: almost always at the middle-management layer, where translation either succeeds or collapses.

We discuss an industry eager to add more - more experiences, more touchpoints, more programming - without considering cumulative effect. “The brain gets confused with too much input,” she says. Luxury depends on intentionality, on knowing what to remove. Brands articulate this principle often. They enact it far less.

Amandari offers an instructive example. The resort sits inside a Balinese village with no walls. Villagers use the property’s paths to reach sacred sites. Managing the hotel required understanding social structure, maintaining relationships with elders, supporting school programs, and navigating ceremonial routes. None of this was narrative embellishment; it was the operational reality.

Liv describes this period as both professional and deeply personal as responsibility extended far beyond the perimeter of the hotel. Sense of place was not an aesthetic layer. It was a constraint, a guide, and at times a boundary that could not be crossed.

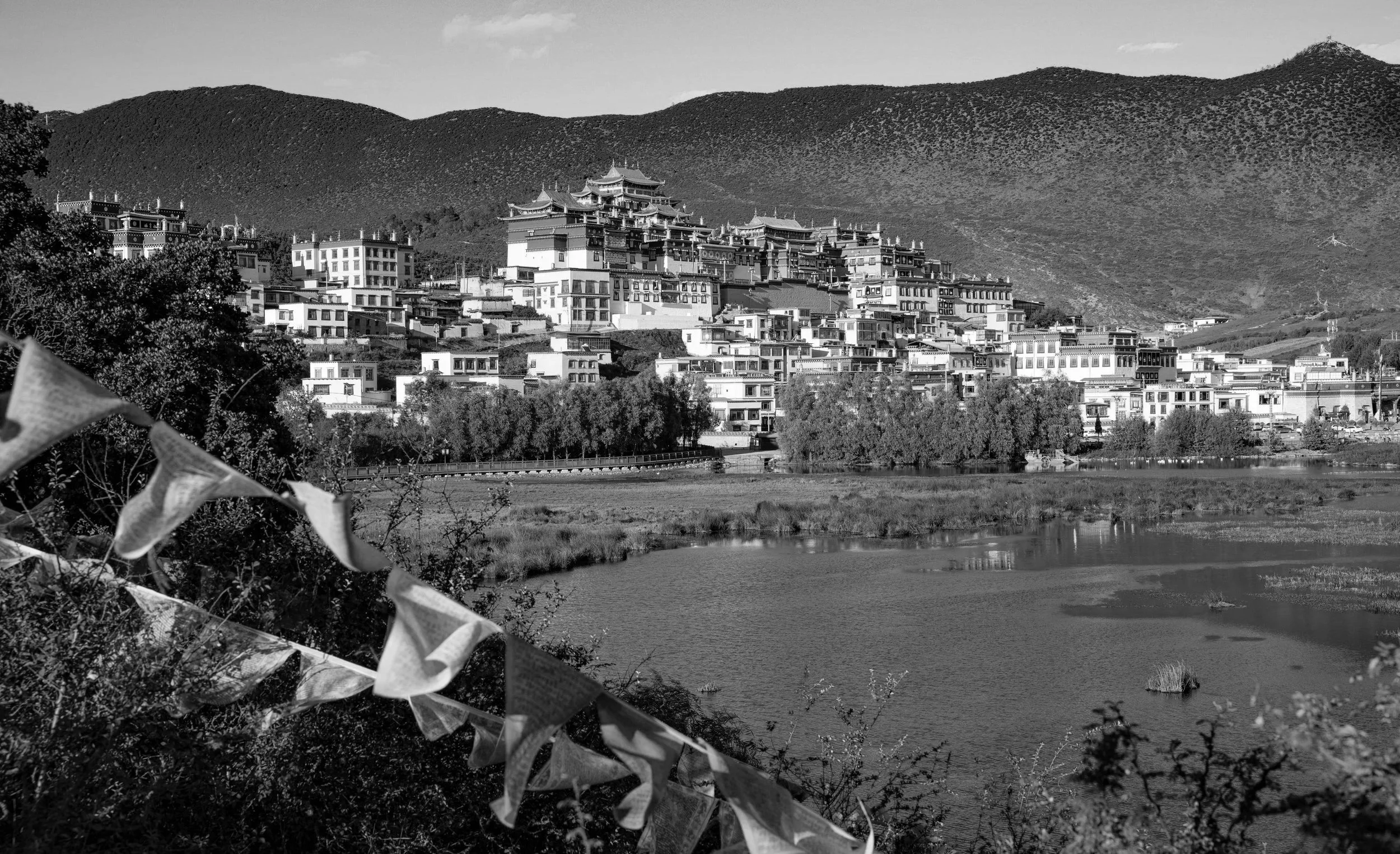

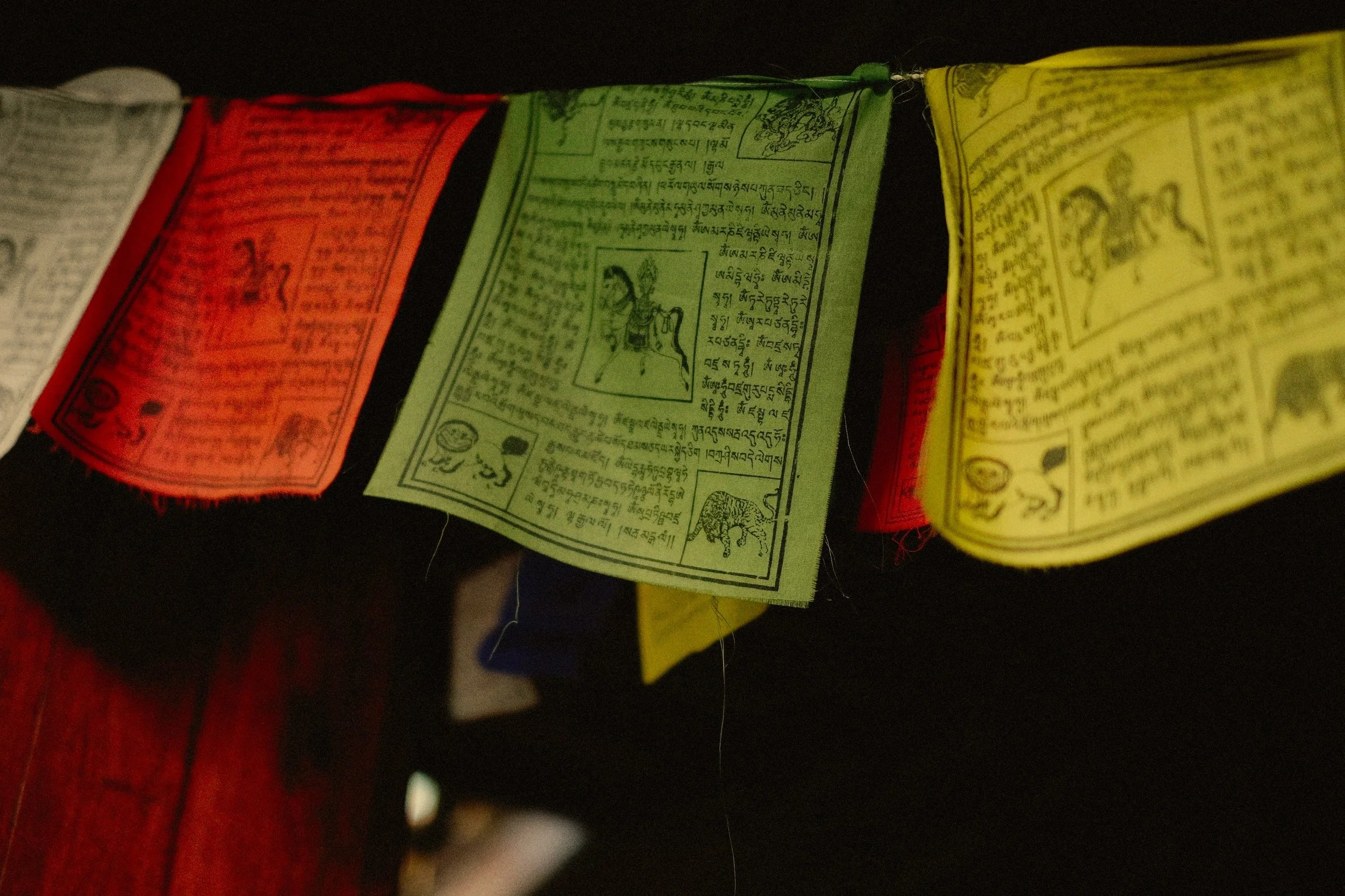

Her Tibet work reinforces this, though at different scale. A Tibetan hospitality company contacted her to write standard operating procedures. The founder - a former BBC cameraman who had worked with Michael Palin -returned to his own country, saw its beauty with fresh eyes, and built a collection of hotels across Tibet and Yunnan province. Instead of delivering documents from London, Liv proposed something else entirely:

She and the corporate team would undertake an 1,800-kilometre journey from Lijiang to Lhasa. Twenty-five days in Tibet. Seven hotels along the route. At each property, she assessed operations, delivered reports, conducted training. The journey itself became methodology. Crossing mountain passes, high-altitude terrain, experiencing the properties in sequence, understanding what each location demanded from its teams. Then they brought everyone - general managers, housekeeping managers, front office managers - back to Lijiang for ten days of multilingual workshops.

"It's easy to write standards, but they usually sit on a shelf," she says. "We needed the teams to own them." Written standards alone change nothing. Teams adopt practices only when they understand the rationale behind them. This kind of transmission is interpersonal, you cannot email someone taste.

The work draws on what she calls operational discipline: "In the operation, every decision mattered: the wrong line on a drawing board could be costly. That discipline, that awareness, that is what forms taste and judgment." The high-stakes nature of operations - where errors compound and small choices echo across years - calibrated her perception. Consulting lets her apply that training, but only because the stakes taught her what to see.

Where the Process Stalls

A UK project she advises makes the pattern visible. The hotel invested twenty-five million pounds in physical upgrades and is investing an equivalent amount in service culture - not afterward, but in parallel. The organisation kept announcing initiatives without changing how staff learnt to read situations or make decisions. "You can't keep doing the same thing and expect different results," she says. They were trying to refresh outcomes while keeping the same perceptual habits intact. Now that those underlying behaviours are shifting - how people observe, interpret, and act - the transformation is finally taking hold.

When I asked her to define future hospitality at its essence, stripped of brand, logo, campaign, she answered quickly: human connection shaped by accurate judgment. Not the grand gestures. We talk about a story from the panel discussion about a massage therapist who intuitively offered personal advice to a guest, someone clearly empowered to respond from trained perception, not script. These acts require trust, training in how to perceive, and systems that make discretion possible. Most organisations provide none of these conditions.

What conversations like this show is that hospitality’s most consequential skills are perceptual, not procedural. They depend on the ability to read a place accurately, understand its constraints, and act with judgment inside them. These are forms of intelligence the industry relies on but does not formally teach.

Until hospitality begins to treat perception as a trainable skill rather than an incidental one, the gap between aspiration and what teams can seamlessly deliver will remain. Luxury at its most coherent remains artisanal because the intelligence it requires forms slowly, through practice, in conditions that take time to build.

Understanding that might matter more than solving it and could be where the future work lies: not in another set of standards, but in developing ways for teams to learn how to see.

words by Jean Linda Balke, photography Liv Gussing Burgess, Amandari Bali