Beneath the Surface with John Jaspers: Where Light Becomes Memory

There is a world-renowned museum in Unna, Germany, that most people walk past without knowing it exists. Standing in front of the building - which houses a library, adult education center, and city archive - all visitors ask the same question: "Where is the museum?"

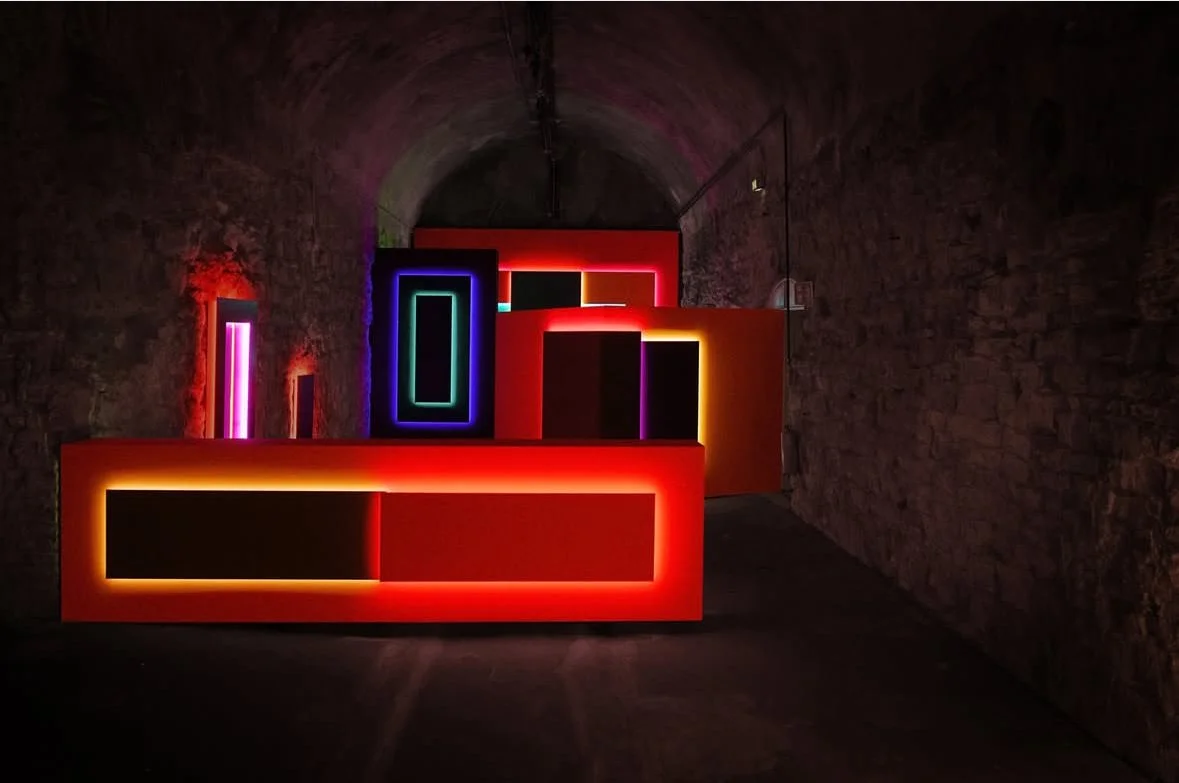

The answer lies eleven meters underground, in the cellars of a former brewery spanning 3,000 square meters, where light itself has become the primary medium of artistic expression.

John Jaspers, the director of the Centre of International Light Art, tells me about the early days of his tenure now that the museum turns 25. Taxi drivers didn’t know where the museum was. Locals once described James Turrell’s Skyspace - the only one in Germany - as ‘horrible concrete,’ often without stepping inside.

Now we’re standing in one of the underground chambers, surrounded by brewery walls that have witnessed over a century of fermentation, now witness to something entirely different.

The Descent

You cannot visit this museum alone. German law requires guided tours because you’re going eleven meters underground which requires security regulations for subterranean spaces. But what could feel like a restriction runs counter to everything our culture of instant access has trained us to expect.

The descent itself becomes a kind of preparation: a passage from the world of natural light into spaces where artificial illumination creates conditions for perception that don’t exist anywhere else. The temperature drops, the air changes. Your eyes begin adjusting to darkness before you even understand what you’re adjusting to.

"It really is an experience visiting this museum," Jaspers explains. "All your senses are addressed. Of course, you see the art, you hear the art, you smell the cellars, you see the combination of the old brewery walls and a wonderful combination with light art. It's in fact a big contradiction."

Light as Material, Not Medium

We’re standing in front of Mischa Kuball’s installation - three disco balls projecting the words "Space," "Speech," "Speed" in rotating patterns. It’s deliberately static, reflecting endlessly with a hypnotic quality that comes from the words themselves, not the movement alone.

This distinction matters deeply to Jaspers. When we mention the popularity of immersive projection experiences, he’s precise in his response.

"For me, a projection is not light art. A projection is something where light is necessary to show something else. And in light art, light is the basic material with which artists have to work."

It’s the difference between using light to reveal an image and using light as the image itself. Between light as servant and light as subject. The distinction feels important in an age when we consume most visual culture through screens, where light is always, only, a delivery mechanism for something else.

Durational Experience

We’re in Rebecca Horn’s "Lotus Shadows" installation. Mirrors moving slowly, casting shifting patterns of light across the walls. A soundscape of overtones and whale sounds fills the space, composed by a collaborator from New Zealand. Jaspers tells me you need to sit here for ten to fifteen minutes to really experience it.

Later, he describes the Skyspace experience: forty-five minutes of looking at the sky through an architectural aperture while James Turrell’s programmed lights shift almost imperceptibly. "You will see colours you’ve never seen before," Jaspers promises.

The museum works against the logic of sampling, of scrolling, of getting the gist. It insists on duration and presence. Yet, the museum has become popular on social media: it’s what he calls a "selfie museum," where the installations photograph beautifully which creates its own paradox: the images that circulate online are advertisements for an experience that fundamentally cannot be captured in those images.

The Sound of Structure

In one of the cellars, Christina Kubisch has created an installation using four beer fermentation tanks, each one a speaker producing its own distinct sound. It’s dark and somewhat primal, reminding me of an interview I recently did at the Institute of Volcanology and Geophysics in Catania.

I was shown there that every volcanic crater on Etna has a different sound based on its structure, different frequencies emerging from slightly different geometries. It is a parallel from completely different worlds: natural phenomena and artificial creation following the same principles. The way architecture shapes sound. The way structure generates frequency.

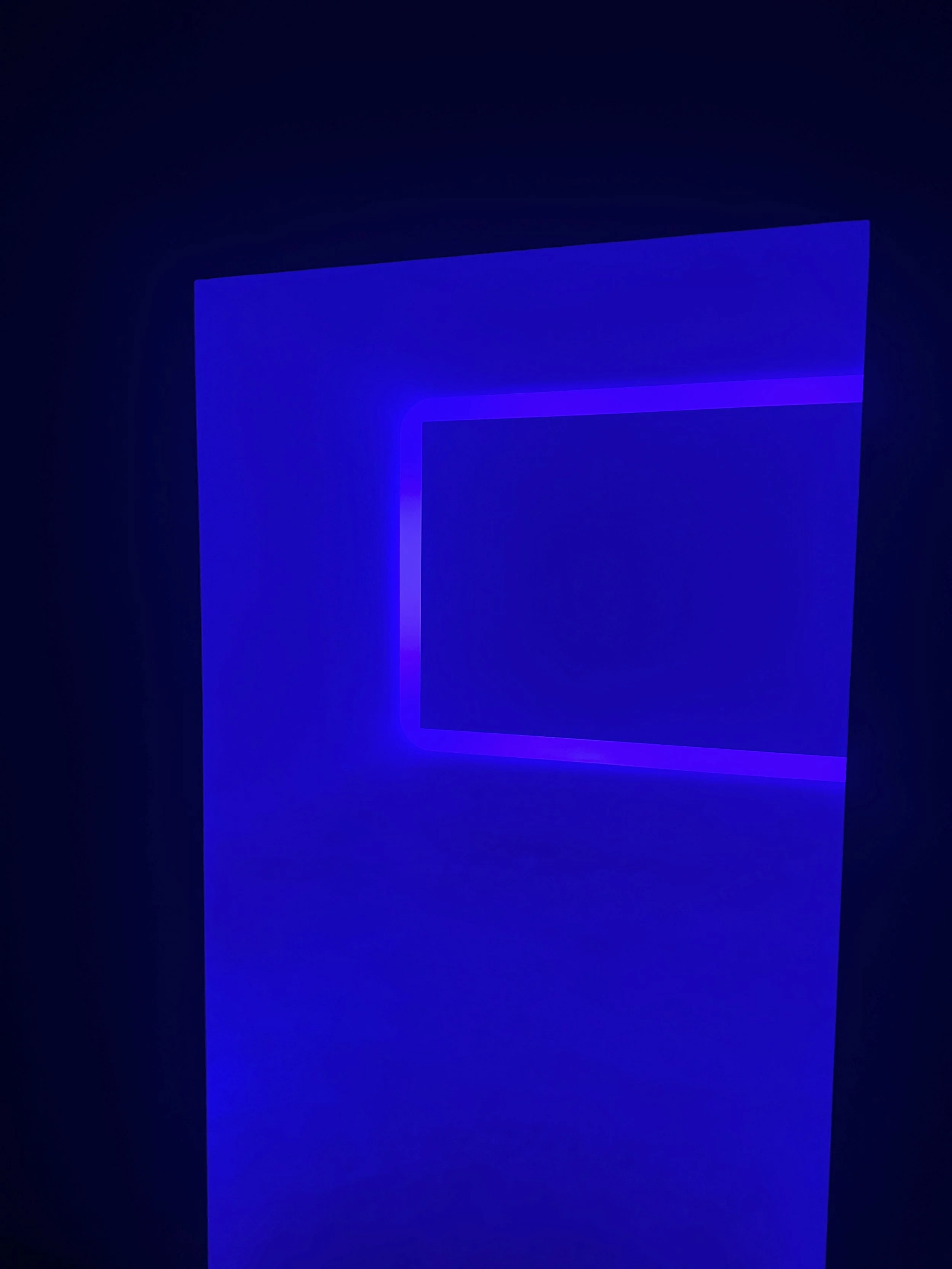

The way light, in Turrell’s work, becomes almost tactile -you feel like you could touch it, though there’s nothing there but photons and carefully calibrated space. When we enter Turrell’s installation called Floater 99, the light seems thick, substantial.

"It’s smells like dry fog," I say. But there is no fog.

"It’s simply the effect of the light and the white," Jaspers explains.

Our senses start inventing information to fill a void. The brain, hungry for data, creates sensations that aren't there. I could have sworn I smelled dry fog, but it was just a memory that my brain put together.

The artwork exists partly in the light, partly in the space, partly in your own neural processing.

Elsewhere in the collection is a work by Jan van Munster: a purple neon piece called "Between Plus and Minus," referring to the space between positive and negative charge, where energy flows. Van Munster once told Jaspers: "At the end of my life, I can summarize my complete life in one line."

The piece itself looks like a waveform, already reduced, already simplified. And when you die, Jaspers explains, the line becomes flat. It is a beautiful metaphor. Light art, perhaps more than any other medium, makes visible the invisible: energy, frequency, the electromagnetic spectrum our eyes can access.

The Emotional Architecture of Light

Jaspers is acutely aware of lighting everywhere he goes. Hotel rooms. Retail changing rooms ("the worst light possible").

"Light is an emotional thing," he tells me. "It literally goes inside of us, we internalize it, and it has an enormous influence. If you have the installation back there with red light, there’s a different feel than when you’re in the blue part with the blue light, or with this light where we are standing now."

Light affects cortisol levels, circadian rhythms, mood regulation, spatial perception. The difference between warm and cool color temperatures is neurological, hormonal, physiological, but also aesthetical.

I mention something I’ve noticed in many contemporary spaces: the in-between areas that don’t work: "You have maybe great lighting in a room here or maybe you have wonderful lighting there, and then you have to go through a hallway that has terrible lighting or a cold draft and it destroys the whole mood. You’ve just been in this setting and then you have to adjust again."

The Future of Light

When I ask about neuropsychology and light studies, Jaspers mentions a major project just beginning with universities in Delft and Berlin, that will go exactly into that, understanding how light affects human perception, emotion, and cognition at a fundamental level.

He also tells me about UNESCO’s International Day of Light, established to recognize light’s growing importance across multiple fields. Not just art and architecture, but medicine.

"Light is going to play an extremely big role in medicine," he explains. "Operations with light beams, they will cut through veins and all kinds of things. There are going to be big, big things where laser light will be applicable for many different things in the medical world."

Light as scalpel. Light as healer. Light as the material through which we’ll literally see inside the body, repair damage, restore function. The museum sits at an interesting intersection: archiving a medium while simultaneously pointing toward its expanding future. It’s both monument and laboratory.

Zigzagging Toward Meaning

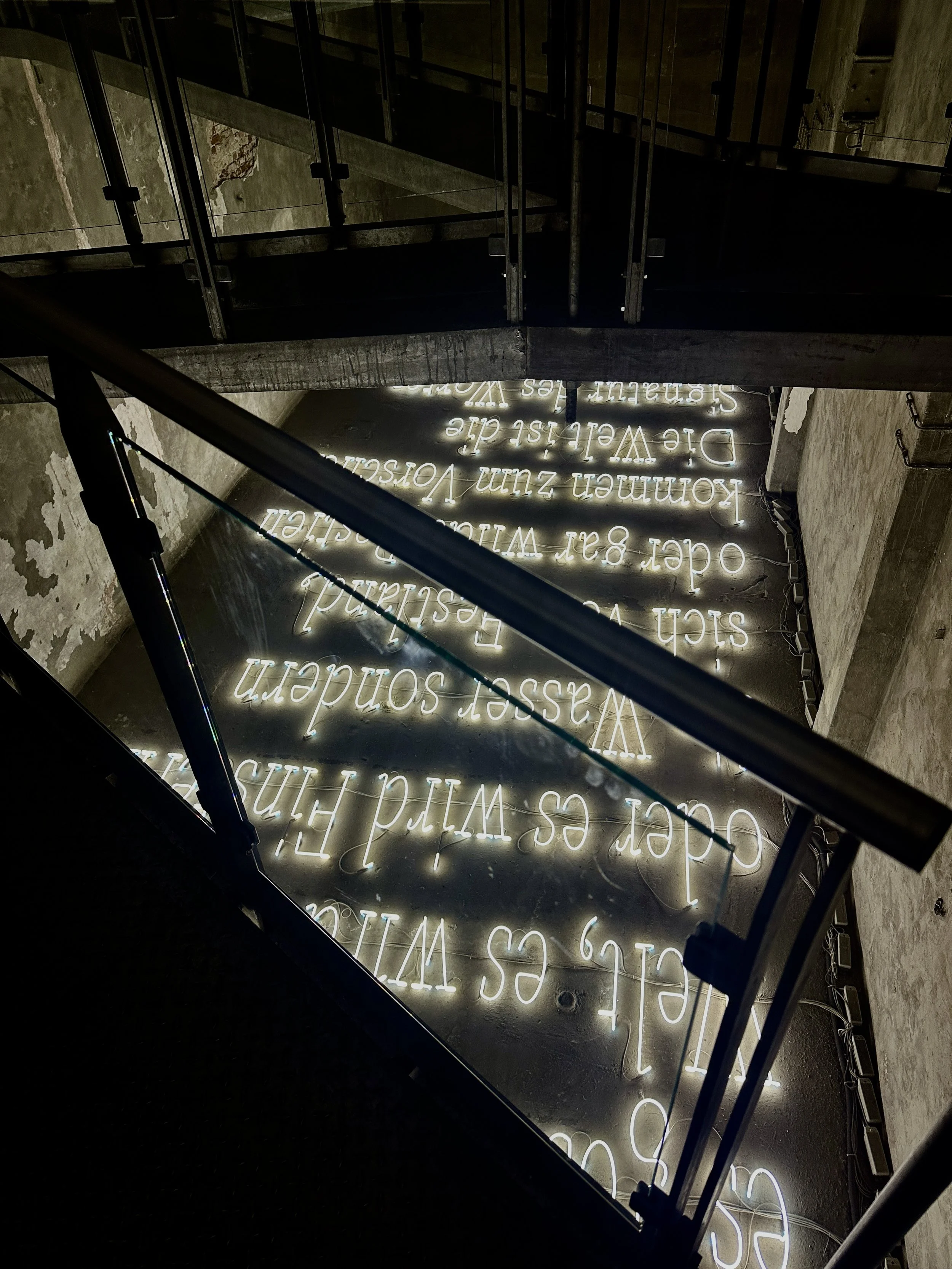

At the entrance to the museum is Joseph Kosuth’s "The Signature of the Word": a conceptual piece using a poem by Heinrich Heine. The text is arranged so you can’t read it in one straight path. You have to zigzag through it, moving back and forth to assemble meaning.

"This is Genesis, how Earth was created," Jaspers explains. "But now it’s not God, but the human being who’s doing it by communicating with each other. People have to make an effort to understand it, and to get it."

This zigzagging feels like the right metaphor for the museum itself. You descend into darkness to find light. You hold still for forty-five minutes to see colors that don’t exist anywhere else. You experience something that photographs beautifully but cannot be captured in a photograph.

There’s no straight path through any of this. Just the slow accumulation of sensory data, eleven meters underground in Unna, in chambers where beer once matured in darkness, light has found a different kind of fermentation. Transformation through time and microorganisms, photons and perception; a slow adjustment of pupils and an even slower adjustment of understanding.

"It’s a museum that you clearly have to experience," Jaspers says.

In an age of infinite digital access, this feels both like a limitation and like the whole point.

words by Jean Linda Balke, photography Jean Linda Balke, Centre For International Light Art