The Story Keepers: Experience as Care

In the Medina of Marrakesh, the streets are a maze of walls. Most façades are blank, their surfaces giving nothing away. Then you step inside, and everything changes: the air, the temperature, the rhythm. A lush courtyard opens, sound softens, and attention turns inward. I always feel like entering a cocoon.

Architecture of balance

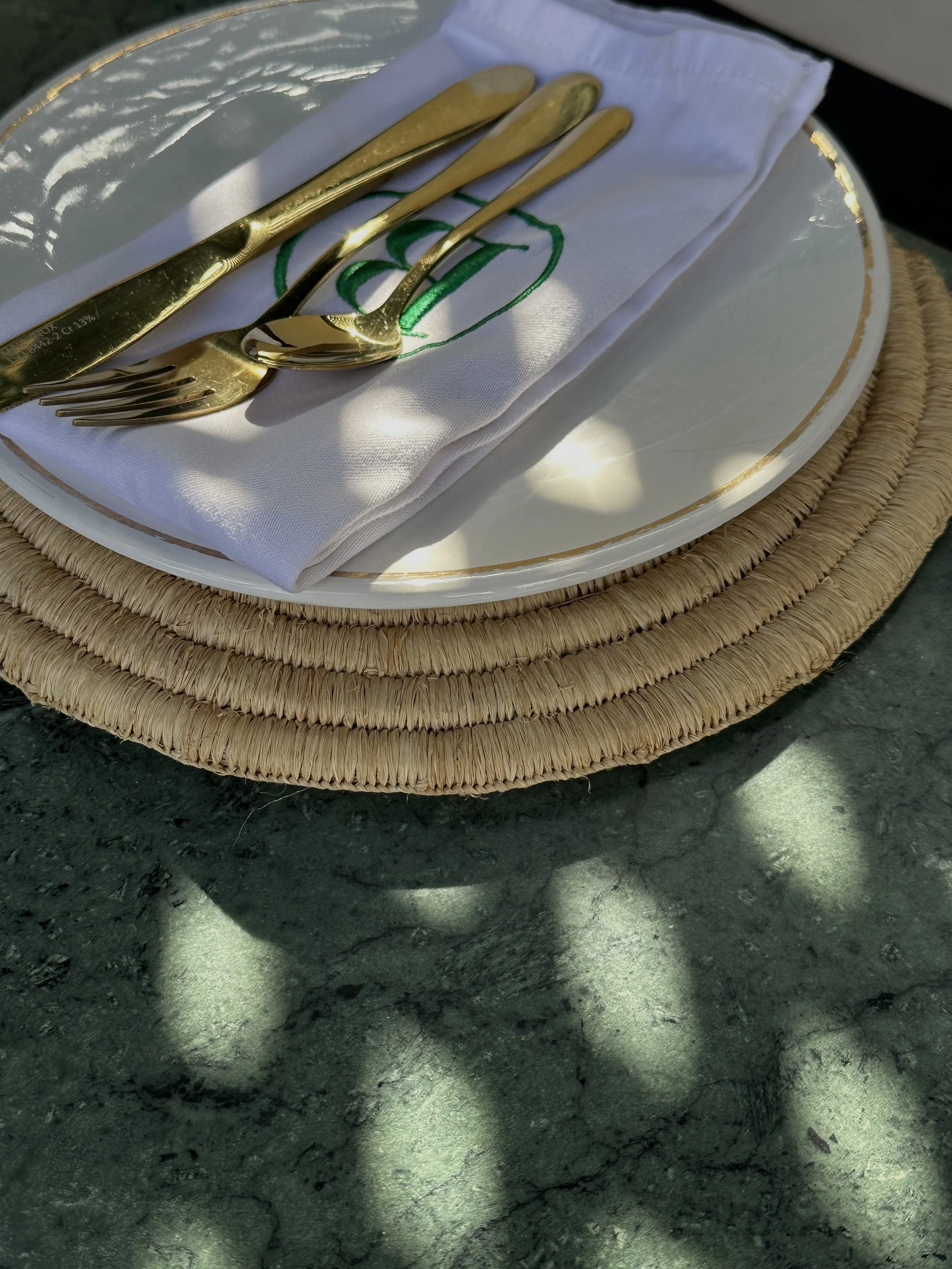

I am at Riad Botanica, restored by Angela Mellak, an Australian strategist and marketer, and her Moroccan husband Mohammed. The couple rebuilt it around an old orange tree that once belonged to the family who lived there for six generations. The house is quiet, balanced, measured in its geometry. The wallpapers are by Florence Broadhurst, an Australian designer whose patterns seem made for the proportions of a Riad. At Botanica, each room carries a name tied to plants and their healing associations: Pomegranate, Orange Blossom, Nella, Rosabel, Zahara.

Angela came to this design project through two parallel disciplines: yoga and marketing. Years ago, a period of health challenges led her to Gita Yoga, a lineage founded in Switzerland in the 1950s and later brought to Australia. Its focus is the endocrine system and the regulation of balance.

Design became an extension of that same philosophy for her: balance as a form of self-love. The renovation of Riad Botanica followed that rhythm: restoring what was broken without erasing its history.

During the renovation, two small birds flew into the courtyard and stayed. She named them Destiny and Fate. “They arrived when the house was still unfinished,” she told me. “It felt like a sign that we were in the right story.”

The voice of continuity

One night she invited Latifa Amghar to tell stories for her guests, participants of a menopause retreat she held together with Annika Glac, titled Artisan Of The Soul.

Latifa, Amazigh by origin, is a young woman with a calm, vibrant presence. We sat down for dinner, and when she began telling the stories, her voice carried evenly through the rooftop. Everyone listened, the evening sky behind her.

She is the only female storyteller working in Morocco today. She studied linguistics at university, focusing on how women are represented in Moroccan proverbs. “Every proverb came from a story,” she told me. “So I went looking for them.”

That search became her practice. She began meeting master storytellers, recording and translating their words. At first she only collected and transcribed. When many of the elders she learned from began to pass away, she started performing the stories herself. “Someone had to keep speaking,” she said.

She memorises each story in Moroccan Arabic before translating it into other languages: French, English, and her own Amazigh tongue from the mountains. “If I don’t learn it in my language first,” she said, “I lose the rhythm.”

Recently she has been returning to villages in the north to speak with older women who still remember the old Amazigh tales. “Sometimes it takes a whole day,” she said. “They forget, they remember, they start again. It’s all part of the story.”

It is important for her to not only keep the stories alive but also the Amazigh language and culture. She is not fond of the term Berber, as Amazigh are also called. She explains that Berber stems from barbarian (a word long connoted with uncivilized), which I hadn’t known.

I find it remarkable that she and many others are keeping local traditions alive without turning them into dogma, as earlier generations sometimes did. She remains open-minded, yet deeply rooted, attentive to the past and sensitive to its misreadings.

Between structures

Listening to her in Riad Botanica, I realized how close her work is to Angela’s. Both build systems that hold and protect something fragile. Angela uses tile, wallpapers, light, and proportion; Latifa uses language and rhythm.

Angela’s design merges Australian openness with Moroccan inwardness. The Riad, as all Riads do, looks modest from the street with just a door and a small sign, but opens into light, colors and air once you cross the threshold. Marrakesh builds privacy first, then beauty, the reverse of how Angela was brought up in Australia I imagine. She took that inversion and made it her method. The pattern of stars and crosses that runs through the tiles connects her Christianity with the Islamic star, the Seal of Solomon in Morocco. She calls it “a conversation between two ways of believing.”

Latifa’s practice works in the same way. She moves between dialects and cultures, keeping each alive by carrying it into the other.

When I asked if she considers herself a performer, she shook her head. “No. A carrier. The story moves through you, not from you.”

Shared forms of care

In both women’s work, care appears as structure. Angela designs for inclusion: a ground-floor suite built for wheelchair users, doors wide enough for access, steps replaced by ramps wherever the old layout allowed. Latifa practices inclusion through language, widening who can understand and take part.

I still remember when I stayed in Essouira ten years ago and trained with a Moroccan silversmith to learn how to make Berber jewellery. In the evening I went to a traditional hammam for women. I tell Latifa how surprised I was: although I didn’t speak Arabic and the women there didn’t speak English, I was scrubbed and taken care of like a five-year-old girl. My hair was combed and oiled against a background of Arabic chatter around me, and I tell Latifa that this memory stayed with me because I felt so nurtured, by strangers (unknown in my Western upbringing). It revealed what care means here: a generosity of community, unsentimental, matter-of-fact, woven through North African and Arabian life.

And in that, a dance between cultures takes shape: one that recognises and honours the other.

words + photography by Jean Linda Balke