The measure of the moment: Roger Saul

Roger Saul has never followed a straight career path. He built Mulberry from scratch, shaped British luxury for three decades, then walked away and began again, more than once. Fashion, interiors, hospitality, now farming: each time he started over with the same precision, but a different purpose. That instinct to move, to build and then change direction, is something I understand and have lived myself.

Life is rarely as linear as success stories want us to believe. It moves in circles, vortexes almost, that keep a red thread but pull you forward, upwards, each time. Saul’s path captures that rhythm: not the climb of a brand founder, but as I understand it, the evolution of someone who keeps re-entering his own work from a different angle.

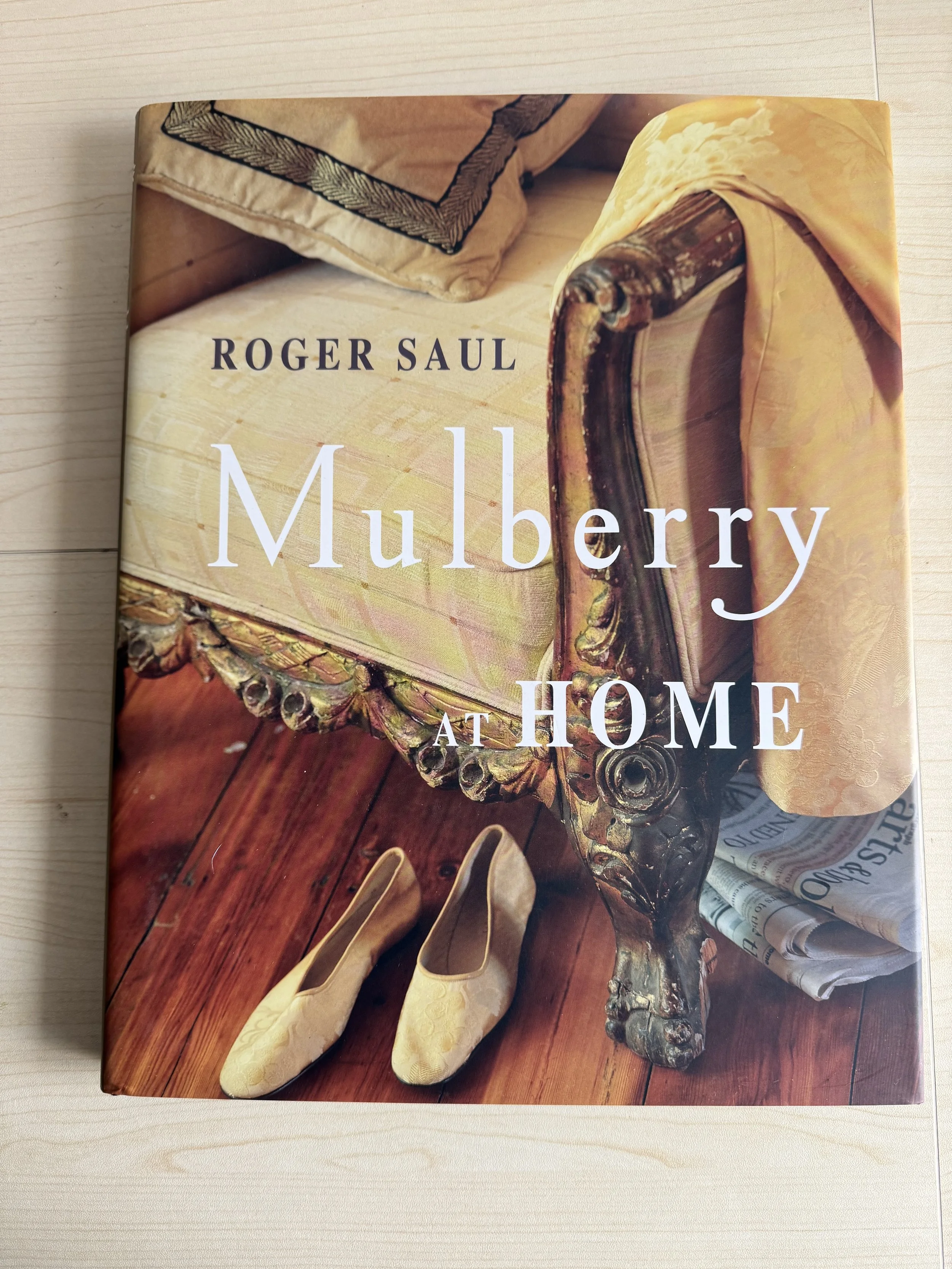

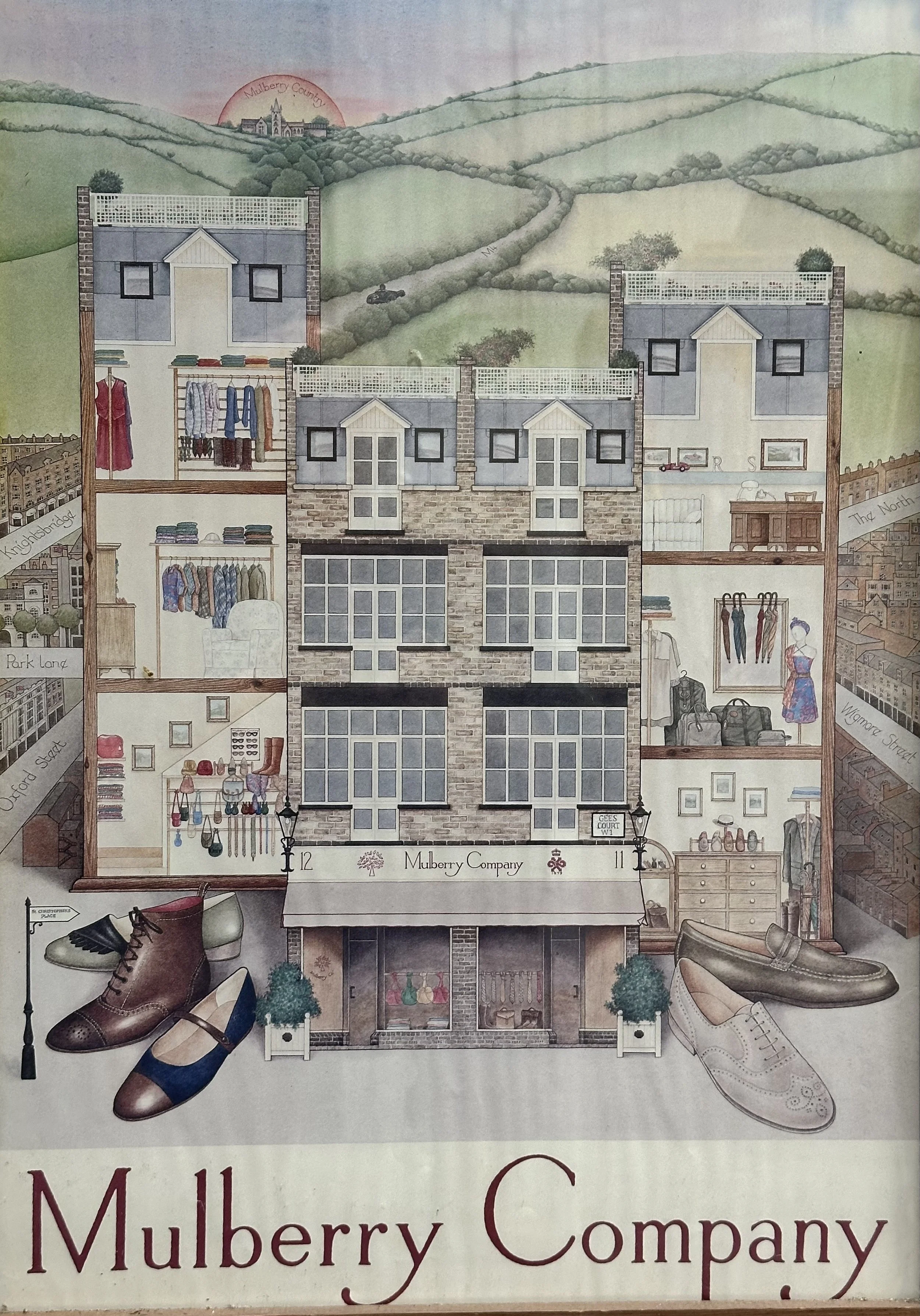

As the founder of Mulberry, the British brand he launched in 1971 with £500 he proved an instinct for enduring design and opportunity early on. Over the decades he built not just handbags but a language of craftsmanship with its origins in hunting equipment. There’s no nostalgia in his voice when he speaks about that period, only understanding of how things had to evolve. We are having coffee after his keynote at Independent Hotel Show in London early October 2025.

“Most of your time,” he says, “is spent creating and preparing the potential for a moment - be it a collection, a store, a hotel opening. If you’ve done it really well, the moment itself is magic.”

The work of building worlds

When I mention beauty as an essence we both don’t mean decoration. “It’s the line of something,” he says. “It could be a London plane tree, or a person, it’s always about the line.” Beauty, in his sense, is structural, not ornamental. It runs through materials, proportions, even timing.

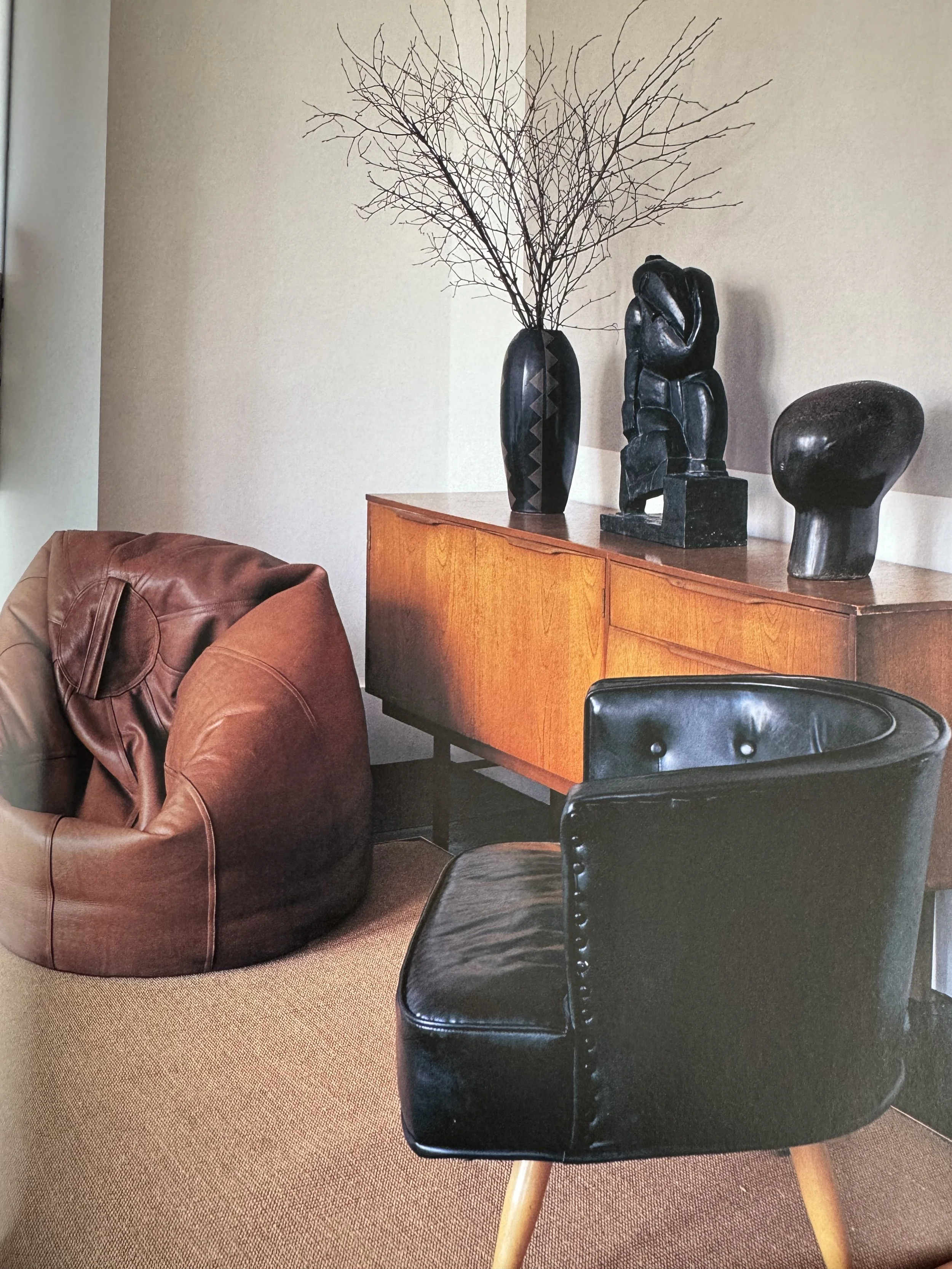

That clarity defined Mulberry’s early years. Saul designed the interiors of his own shops - oak, leather, brass - every element carrying the same tone as the product itself.

Later, he extended that world through Charlton House, a boutique hotel and spa in Somerset, furnished entirely with Mulberry Home designs. Guests would ask to buy the curtains straight from their rooms. Within a year, the restaurant earned a Michelin star.

“Looking back,” he says, “it wasn’t about creating a thing. It was about creating a world.”

The discipline of retreat

What interests me is how he moves between those worlds and how he knows when to stop, sell, and start again. Society loves a success arc that climbs forever, but most lives follow a different rhythm, the ebb and flow, the ups and downs. Once you’ve reached a certain level of success, starting over or even admitting a downturn is rarely discussed openly.

I like that about him. He’s candid about the moments he misjudged: times when he saw problems coming but didn’t act early enough, when an exit could have been cleaner or clearer. It makes his story more human, and his later choices more deliberate.

“The biggest thing,” he says, “is to know when to retreat as well as when to advance. That’s the hardest part.” He recalls selling his organic spelt business at Sharpham Park after losing his European market. “I could have carried on,” he says, “but my sons weren’t coming into the business. I had the money, but why? You need to close it, sell the big old house, sell the farm, and exit cleanly.”

In a world obsessed with growth, this kind of clarity and willingness to stop feels almost radical.

From leather to soil

Sharpham Park, his 300-acre estate near Glastonbury, is now his main focus. Known first for reviving British spelt and now for cultivating organic walnuts, it’s both a business and a philosophy - a continuation of his lifelong respect for material integrity.

“What fascinates me now,” he says, “is regeneration. The idea that beauty can be restored if you treat the system with respect.”

He talks about the land as he once talked about leather: texture, patience, care, and although it seems like a completely different industry, I feel it isn’t a departure from luxury (when you connotate it with quality and care) but a evolution of it. In a culture driven by novelty, Saul’s work argues for the value of rhythm and of staying long enough to understand what’s in front of you.

He mentions the house he’s building on the estate as sustainable, elegant, and self-sufficient. “It should grow out of the land,” he says, “not sit on top of it.” The sensibility that shaped Mulberry is still present, only now translated into structure and soil. I recognize this as a true artist’s approach, one I know from goldsmithing, creating photography, short films, and other forms of work:

To reach the essence of something true, you strip away the noise instead of adding decoration on top.

Facing the artificial

When I ask him about technology, he becomes reflective. “AI is here; we can’t escape it,” he says. “But the balance is difficult, especially for the younger generation. There’s so much information, yet we no longer need to go anywhere to experience it. We’re doing it all in here now.” He taps his temple.

He worries about a world where connection becomes simulated and travel optional. “The joy of my life,” he says, “was meeting people across cultures, across borders. I fear we might lose that.”

I tell him I see a counter-movement in my conversations with young people: they are searching for something tangible, wanting community and presence again. He nods. “That’s good to hear,” he says. “Maybe that’s where hope lies.”

The long view

When our conversation ends, he gathers his notes without hurry and we part ways.

His life from what I learned about it reads like craft: moments of precision, pauses, the courage to begin again.

Maybe that’s the work of anyone who keeps making things: to prepare the ground, again and again, until the moment arrives. Magic.

And perhaps that is the new shape of beauty: awareness, conscious creation. Saul’s life suggests that luxury, at its purest, is the ability to edit: to know when to stop, when to hand things back, when to let the next line emerge.

words by Jean Linda Balke, photography Roger Saul and Sharpham Park